Microbes revived from eternal ice pose a climate risk

Scientists at the University of Colorado have succeeded in reviving microorganisms that had been in a “dormant” state within ice layers for many years. This was reported by Zamin.uz.

Samples for the study were taken from special tunnel walls located in Alaska, more than 100 meters deep. The preservation of ancient animals — bison and mammoth remains — in the tunnel walls confirms once again that this area is a natural archive.

According to the scientists, the unpleasant odor noticeable upon entering the tunnel is related to the metabolic activity of the microbes. They collected several samples estimated to be nearly 40,000 years old, added water to them, and incubated them at temperatures ranging from 4 to 12 degrees Celsius.

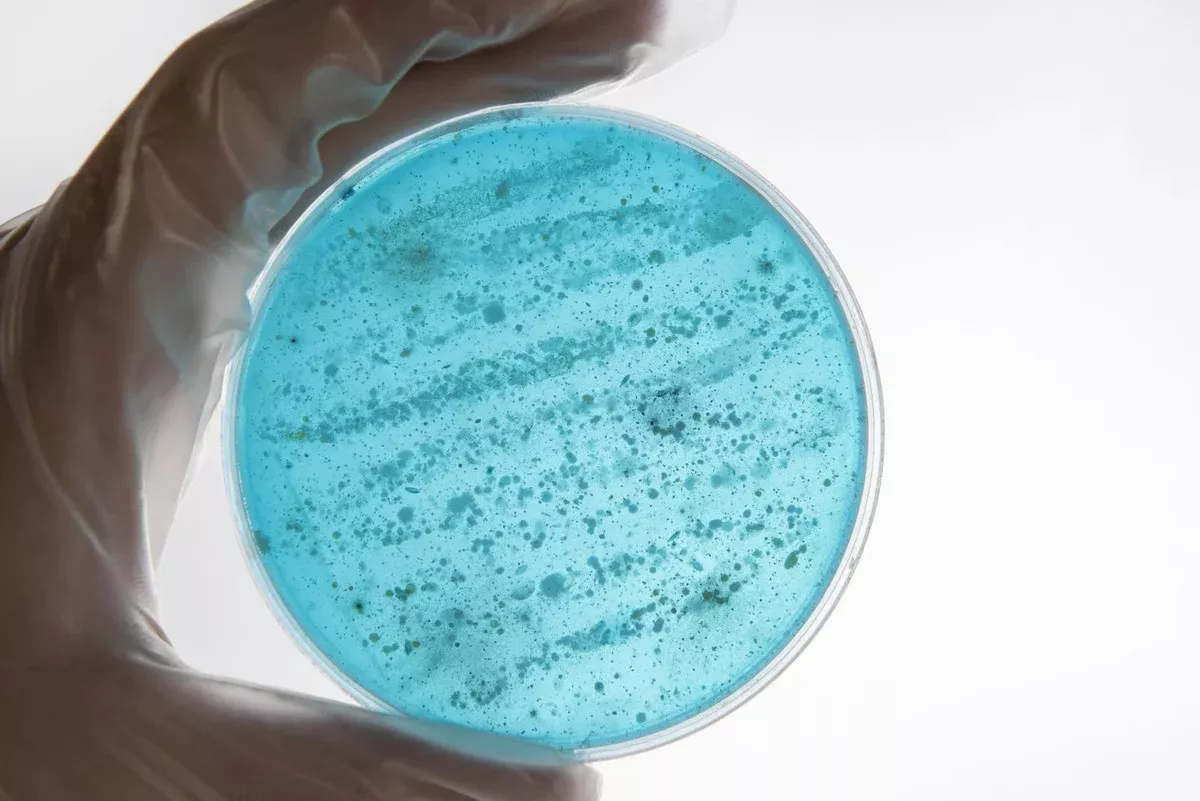

As a result, the microorganisms gradually came back to life and formed visible colonies under laboratory conditions. Interestingly, the microbes emerging from the ice do not start activity immediately.

It takes several months for them to reach full activity. After that, they begin to decompose organic matter and release carbon dioxide.

This process deeply concerns climatologists because the activation of microbes as permafrost melts could increase greenhouse gas levels and accelerate climate change. Permafrost is a mixture of soil, ice, and rock that has remained frozen for years, covering about a quarter of the Northern Hemisphere's landmass.

This layer acts as a time capsule, preserving millions of bacteria and other microorganisms in a frozen state along with animal and plant remains. Therefore, if permafrost melts rapidly, a large portion of past biodiversity may mix into the modern environment.

Laboratory experiments show that microorganisms have a high potential for viability and metabolic reactivation. This raises a major question: if permafrost loses its stability and large areas thaw, will this not add extra pressure on the natural carbon cycle?

Scientists recommend taking precautionary measures in advance. Continuous monitoring of permafrost conditions, measuring underground gas emissions, updating biosafety protocols, and improving risk models are necessary.

Because this issue directly affects not only geology or microbiology but the entire global climate system. According to the scientific community, the results of such research will be of significant importance in future policies for managing natural resources and assessing risks.